Hi folks. This is an essay from a project I call The Baker Maker Roadshow. On a vintage bicycle with a banjo, ingredients for biscuits, and my overalls, I set out to ride rural roads in my native state of Arkansas. My hope was to cold-call homes, meet people, cook for them, and somehow connect my present-day Vermont life to my roots through shared food.

Below you’ll find the story of an afternoon I spent baking, playing music, and sharing stories in the town of Jethro. Before the piece there is a little additional background on this biscuit-powered adventure. I hope you enjoy.

Martin

Elkins to Breshears, Combs to Crosses, Cass, then over the Mulberry River; I’m pedaling south on State Highway 23, Ozark-bound. The road — a pavement spit, with knots and twists — is asphalt on borrowed time. The forest, kudzu, ticks, and heat, will eventually rise, climb, smother, and subsume. Everything returns to red dirt.

Once colloquial, now branded “The Pig Trail Scenic Byway,” State Highway 23 used to be the best connection between Northwest Arkansas and the state capital, Little Rock. But, it’s been bypassed by wider lanes, cruise control, and blurred views; a mighty effort to avoid hairpin turns. There is no shoulder or room for hurry and worry here; take your eyes off what’s ahead or grab the wheel after beers and the woods will watch, unblinking, as first responders peel you off a tree. But, if one travels at Pig Trail speed there are rewards.

Afternoon in Jethro

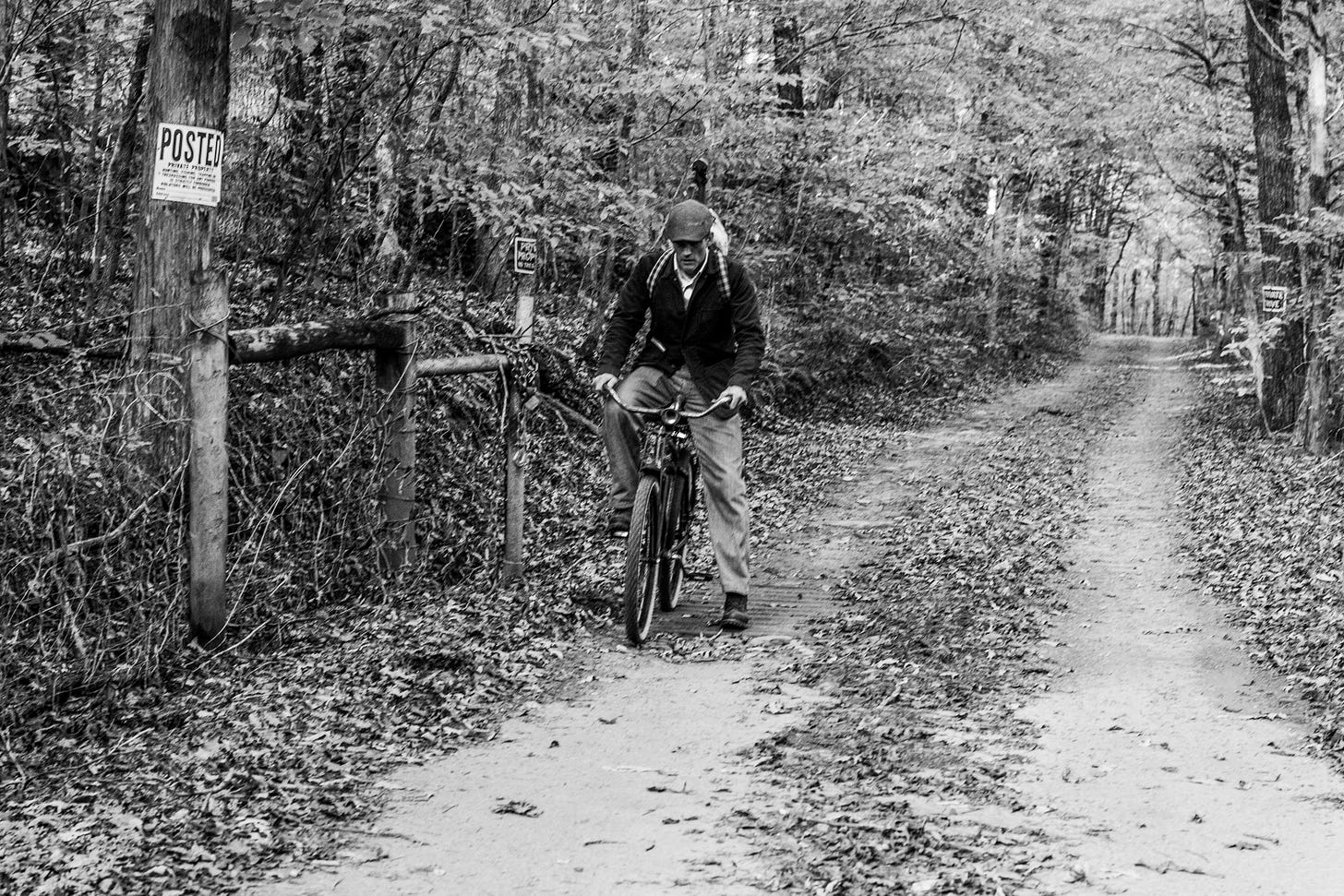

Out here on the Pig Trail, where “traffic” means scissor-tailed fly catchers riding grasshopper bumpers or red ants, queuing for a hill hole, an event like me doesn’t squeak past daily. I’m a sight: banjo on my back, old-timey clothes, and a rusty bicycle with a wicker basket.

Don’t let appearances fool you. I’m no tax collector, or evangelist — I sell nothing, collect nothing, preach nothing — you have no debt with me. For you, my offerings of fresh biscuits, molasses pie, and live banjo are all-inclusive. Please have seconds.

But I can’t find takers. Maybe the people here are shy, or their house is a mess, or maybe he’s weird? Though I grew up in these hills, they hesitate. I knock at the door, the dogs go nuts, I see movement — a flick of a curtain, a shadow jumping behind the house — but then...nothing. I keep trying.

I thought this might happen. I tried to warn people along the route with ads and paper signs announcing: “Coming soon! A baking, biking, and banjo adventure.”

Yesterday I did make it inside the home of some hippies that live and farm on top of a mountain near Brashears. Over home-cured meat, warm biscuits, and fresh pickles we talked of lynchings, Marshallese immigrants, and the ways culture, religion, and politics intersect at the farmer’s market. “We talk about our gardens,” said Donna. Regarding insects which eat plants regardless of the farmer’s faith, creed, or ethnicity, Donna offered, “We all have bugs.” When the talking gets tough, pests are neutral territory.

This morning, dreading more door-knock roulette and the potential for loaded barrels, I’m trying something different — I’m cold-calling people on the telephone. I don’t like it. But I sort-of planned it this way and even if it sucks, I’m here and I’m not leaving. I put off the calls, I pace, I stare at the phone — I pace some more and finally get the guts to dial.

“Please leave a message.”

“Hello, my name is Martin Philip, I’m in the area, talking to people and making food — I’d love to set up a time to come by and meet you.” I leave my number and, within a minute or so, the number I called rings back.

“Hi Martin, this is Sandra,” she says in a tone which is the vocal equivalent of sorghum syrup. “Hi, Sandra.” We make small talk. She’s reserved, I have the enthusiasm of a game show host.

I try to invite myself over. She’s hesitant. “We’re busy,” she says. And then, “We have flyers to stamp for the fire department.” And, ”My husband’s out hunting...” By the sounds of it I assume she will continue with something like, “We just painted the doorknobs, nobody can get in the house.” “We’re fumigating.” “I have the plague,” and so forth. Any other day I would stop bugging her. What jerk would press someone to let a stranger into their home in the boondocks of the Ozark Mountains? Me. Today. I would.

Sandra and Mack’s number came from a neighbor. They are “life-long residents — Mack helped us get started baling our own hay. He’s quite the story teller, and never politically correct…”, she wrote. “He stops by periodically to sit on the porch and share the latest community news.” My hope as I dialed the number was that they might provide a view into my unknown — a way of living, thinking, voting, praying that I don’t understand.

“I’d love to make you some food,” I suggest, “or, I can help you with the flyers…” Silence. “What food do you make?” she asks, more curious than inviting. “I can make biscuits, grits, or some bread...” “I don’t like grits...and I make my own biscuits and bread.” Uhhhhhhh...“I could bring some beans that I made?” ”I’m on a diet,” she counters. Alright, alright. At this point any further pressure would be rude. I change my approach.

“Sandra,” I say in the warmest, kindest baritone that I can muster, “I’m interested in the way that food binds us — the way that we use meals to celebrate, to soothe, to come together. These are conversations I would have had with my grandmother, but she passed. Maybe your husband would put up with a bowl of beans and some of my biscuits for lunch? I’ll do the dishes.” Pause. Pause. Pause. “Well...alright...” We schedule for noon.

I pedal a side road looking for the the intersection of Upper Jethro and Lower Jethro road, in the very town of Jethro. I laugh as I ride, thinking, “Who was the mountain of steaming man that began this Jethro place?”

Some yippy dog the size of my boot chases me, barking death threats with a loose Angus steer in tow. The dog gives up just shy of where dirt crosses the pavement of State Highway 23. Maybe it knew the tabby that was struck at the intersection this morning — long hair blowing in the breeze, glazed eyes, dead on the shoulder.

Ahead there is a long hill. I build speed and settle into a rhythm, biting chunks of the climb with each rotation. I look left — yellow sun from the south backlights a field; a silhouetted lone oak ringed with cattle chewing cud. Queen Anne’s lace and barbed wire fill the foreground. I’m in love with home again.

A noise approaches from behind and a large SUV heaves past, iPhone pressed to the window, filming. I can’t wave, I’m cranking like Lance Armstrong on the Alpe d'Huez, but I flash my best smile and shrug. I don’t know what’s happening here, either.

I make the rise and the road flattens for a brief period of rural, no-hurry pedaling. A small cluster of homes fades off the back of the bike and peace settles...but is immediately broken. I hear a sound I’ve eluded thus far. It’s the deep hacking bark of a country mutt woken from sleep. I curse under my breath and squint to see that not just one, but two, have set chase.

I pedal as quickly as possible. The basket and its contents clank, my jacket flaps in the wind, the dogs run like dinner depends on it. But after a half mile or so they realize I’m too stringy to enjoy and return to snapping flies in the shade. I pass a cemetery then bounce into the rocky driveway of Sandra and Mack’s farm.

Mack sits on the bed of his truck smoking, wearing his hunting coveralls. He’s a hulk of a man. His granddaughter jumps around the yard like a pony playing make-believe with broken-down tractors, discarded toys, and farm tools. I consider topics for ice-breakers with Mack and choose hunting. We talk Chronic Wasting Disease, stand placement, and the “button buck” that he let pass this morning. Maybe my experience as a hunter gives me some credibility, maybe it doesn’t; it’s impossible to tell. Sandra comes out and we wind our way through the carport to find the kitchen.

I set the butter beans I cooked over a campfire with smoked pork rib meat to heat on the stove and work on biscuits to go with them. Sandra is over my shoulder a little. As she hand-cuts red potatoes, frying them in a skillet with oil, fresh onion, and salt, she offers that my biscuit dough looks a little dry. She’s right. She notes that I should cut them with her special drinking glass, and she shows me a plate of her own that she had already made (“These are my biscuits”). I get the sense that I am on posted land. Meaning, this is her kitchen — she does the cooking and baking here. If you are a stranger passing through Jethro intent on a baking coup, keep walking, Bub.

I take it in stride. Sandra and Mack are enjoyable and I know I can make a mean biscuit. At 20 minutes I peek into the oven. They look ornery — deep golden tops, flaky, bran-flecked middles. The beans come to a simmer, I check to ensure they are swimming in a hot tub of pork fat and juice. Sandra offers plates — I suggest bowls — it’s accepted but doesn’t go unnoticed. I can feel her thinking, “runny beans…hmm,” as I head to the table with biscuits, and bowls.

If I’d been thinking I would’ve been prepared for what Sandra might do before she eats. We sit. I look at Mack, Sandra looks at me, Mack looks at Sandra. Sandra straightens up, puts her hands on her lap, and asks, point blank, “Do you pray?” It feels more like, “Are you churchgoing, and god-fearing?”

Here’s the thing. I grew up a churchgoing regular in a close community of families. Sweet wine, gatherings with food, abundant music…it was perfect. Prayerful, even. But while the foundations of that experience remain in my life, I do not pray. Or go to church.

In the milliseconds after her question, I have miles to go. I consider the secular verse we offer at our family table. While it feels adequate to me, my read of this situation is that it will fall short.

But hold on. Who owns prayer? Who can define how we speak, feel, connect, or identify with God, gods, goddesses, or nothing? Do I need a certificate to pray? What are the rules? What is required to launch gratitude, awareness, thought, love, or positivity into the universe? Can I say something in Sandra’s language and mean it in mine? Yes.

Do you pray?

I take a moment of silence and this is what comes out with all of my honest heart: “Lord, thank you for gathering us together today. Please bless this food and this community. Amen.”

“Amen,” they say. And we pick up our spoons.

Mack reaches for a biscuit, and busts the silence with “Dig in bud!” We gather up our first bites. “I’ll get hungry ‘bout this same time tomorrow, too,” he says with a wink, dunking the crisp biscuit into the runny beans with his baseball mitt of a hand. Sandra laughs deeply at his suggestion. She’s sincerely amused — but might also be thinking, “Oh, hell no...” I’m not sure yet.

“If I’d a shot this mornin’ we’d had fresh deer meat,” he offers in a voice so deep that it sounds like it begins someplace underground. I’m fascinated by Mack. If an animal moves, he knows how to cook it.

“What’s the first thing you eat [from the deer]? The heart?” I ask. “Backstrap...and neck,” he replies, without hesitation. Backstrap, also known as loin is obviously a crowd favorite. But neck? “I like the neck. I take mine and debone it. About an hour ‘fore it’s done I add potatoes and carrots – she likes carrots – and let ‘em soften.”

“What about groundhog?” I ask. People always want me to get rid of them — I won’t do it unless I plan to eat it. “I like it,” he says — Sandra makes a sour face. “But how do you cook it?” I ask. “Oh, just like coon,” he offers. I feel officially accepted as he applies the honorable assumption that I know how to cook raccoon.

The food memories that pour from Mack’s veins spill Muscadine wine, wild turkey cutlets and home-cured ham into the kitchen. The rock stack foundation of his grandma’s house on the hill loses stones to the dirt each year but somehow his memories of meals and gatherings thicken, and rise. “You ever tried beaver?” he asks. “Beaver is good. I take the front legs, and the back legs and parboil ‘em with oranges and carrots — something to take the wild out — [then] I pull the meat off and put it in the oven with barbecue sauce on it.” And on, and on, and on.

We reach a comfortable lull, crunching to the last biscuits with Sandra’s Muscadine jelly. I reach for my banjo and she offers that her father built instruments — she has a fiddle, mandolin, and banjo, all made by his own hands. She produces that exact banjo, too long neglected to play, and also brings her store-bought one: a gilded showpiece. I tune it and begin to play.

As my hands move I hear a commotion around me but continue; the sound from the heavy resonator crackles in my arms, punching and cutting across the kitchen. I realize, as the background noise keeps on, that it’s coming from Sandra and Mack. They are hollering and laughing — my lead-off, “Cripple Creek,” was her dad’s favorite tune and the first thing he ever played for Mack. Sandra runs for her guitar and joins in. One song leads to five or ten: we harmonize through Denver’s “Country Roads,” some gospel, “God on the Mountain,” (“My favorite,” she says) and finally, her moody version of “House of the Rising Sun,” sung with the words to “Amazing Grace.” The minor key is appropriate — grace, forgiveness, salvation, and atonement are fraught matters.

I ask if I can take their picture before I go. We walk out to the yard and find a lilac bush that must’ve lightened a dooryard a century ago. Today it soaks the sun, watching you and I as we fight and make up, judge and forgive, eat biscuits and get on with it.

They wish me luck as I swing my leg onto the bike. Sandra, half-stern, advises that “most women in the Ozarks will not let a man come into their kitchen and cook.” “Point taken,” I say, and turn right to avoid the dogs on my way back to the Pig Trail.

For more work from the Roadshow, here’s an audio version of a story that ran in The Kenyon Review entitled, The Healing Stone of Mountain Creek.

I love listening to you, Martin. Listening to the hearts of people is a treasure. Family and community are to be cherished.

Wonderful! The story and the storytelling. I love your writing - it is so immediate. Thank you.