We’re full steam to fall here in Vermont. If you missed the caramel apple buns, now would be a great time to try those out. We had them for a birthday celebration last week — they’re the perfect cinnmon, apple, and creme anglaise aromatherapy for the season.

And speaking of favorites, I’m here with a large, bran-crusted sourdough loaf that is loved at my house. If a classic sourdough miche were raised in Italy by ciabatta parents, it might come out something like this. Abundant in size with an open crumb and crusty vibe that says, wood-fired, and rustic, it’s truly a loaf for the whole week. Or even the whole year.

Remember that you can support the work here — the recipes and methods, the words, photography and video. Your help keeps the content coming, and even more, it’s a way to show that you value what’s happening here. I appreciate it!

Let’s get to a short bit of writing and one of my all-time favorites, Pane Casareccio di Genzano.

In 2015 I was baking around the clock. In addition to my regular bakery shifts, I was also practicing my competition breads in a bid to be chosen to represent the U.S. at the Coupe du Monde de la Boulangerie (“the Olympics of bread”) in Paris.

Each day when I left for work, or went back in the evening to mix preferments or do set up, my young son, Arlo, would squeeze me as though I’d be gone for a year. “Good luck, daddy! I hope you get to Paris.” His words held the sum of everything: the support, the effort, the hope, and the lengths necessary to pull it off.

Bear with me here because I’m going to skip a big chunk of the story. The tryouts happened, I advanced to the final round, and I wasn’t chosen.

In some ways I never recovered from not making the team. It wasn’t so much the losing — it was more that all my effort, plus all the support of friends, family, and colleagues, and the countless hours I spent over the course of a few years, wasn’t enough. Everything I could do — all of me — wasn’t enough. I wasn’t enough.

But, sometimes things are more complicated than winning or losing. There’s a proverb attributed to Lao Tzu that speaks to this. It’s the story of the farmer that lost his horse. After it happened, the neighbors came by and said, “Oh, that’s terrible that you lost your horse.” And he responded, “Maybe.” The horse returned after a few days with a second horse trailing it. The neighbors came by, “Oh, great news, you now you have two horses.” “Maybe,” he said. His son broke his leg trying to train the new horse. “Oh, not so good,” the neighbors said. But then the military showed up to send healthy men to war. The son stayed home.

Oh, it’s too bad Martin didn’t make the team. Maybe.

Not being chosen meant that I got my life back. Rather than stepping directly into another long phase of training for the competition, I emerged.

At each round of the tryout process I presented the judging panel with large format photo books (stunningly designed and photographed by Julia Reed) containing my bread formulas, pictures, illustrations, and bits of writing that read like small poems or odes to each recipe. With time on my hands, I started showing them to friends and family.

One person suggested that I might be a decent writer. Another thought what I had could become an actual book. And another — and this was very fortuitous — connected me to a literary agent. And somehow, some way, a miraculously short time later, I was in New York, talking to publishers. And soon after I had a deadline, and a book to write.

And so I started. Writing wasn’t a practice I’d ever had. With a background in classical music, I had no idea where to begin. I found a writing consultant (Sarah Stewart Taylor, a great author in her own right who made the project successful in 1,000 different ways), and a therapist. I embraced Sarah’s writing advice of “show, don’t tell,” and tried to convey a story. In doing so, I traced a line from where I began, through all the ensuing challenges, and onward to a new life that connected my heart to my hands, and my soul to my mouth.

Breaking Bread was published in 2017 with the goal to help people bake more flavorful, and beautiful things and, more importantly, with the hope that it might inspire all of us to connect our own hands to our own hearts, baking our narrative along the way.

In looking for a bread to highlight from the book, I came back to Pane Genzano (known by its full name as Pane Casareccio di Genzano, one of only six DOP breads in all of Italy). A large, bran-crusted loaf with a very dark bake and a light, moist interior, it gives off the unique aroma of coffee roasting (caused by the bran crust toasting during baking) as it bakes. Full of sourdough culture, the bread keeps as well as a wholegrain miche, but eats more like ciabatta due to its open crumb structure and white flour.

When I say, dark bake, you don’t have to take it as far as they do in Italy (but you should). Do have a look at the color in this video as a great reference for the style of this gorgeous loaf. The full bake and slight bitterness is the perfect accent to the malty, lightly acidic crumb. I think you’ll love it. No maybes.

Pane Genzano

Yield: 1 large loaf or two smaller rounds

This is a two-day bread. On day one you’ll set a stiff levain preferment. On day two you’ll do the final mix, bulk fermentation, shape, and bake. There is a small amount of yeast in the final dough — if you want to omit it, make sure that you have a sourdough starter in peak condition and adjust your bulk and final proof times accordingly. Part of my joy in this loaf is found with the lightness and ciabatta-like attributes which are, to some degree, afforded by the commercial yeast. Be sure to give it an ample amount of fermentation and rise at each stage; as I always say, watch the dough, not the clock.

Stiff levain

All-purpose flour, 164g

Water, 99g, tepid (75 to 80°F)

Sourdough culture, 33g

In a medium bowl, combine the tepid water and sourdough culture. Mix until combined, then add the flour. Mix briefly, then knead until smooth.

Cover and set at room temperature for 12 to 18 hours.

Final dough

Water, tepid, 395g

Stiff levain, all

All-purpose flour, 493g

Salt, fine, 13g

Yeast, instant, 3g (1 t)

*Coarse bran for the crust, about 100g or so. Check your local natural foods store, it’s often available and very cheap in the bulk section. Lacking bran, sesame seeds are a decent substitute.

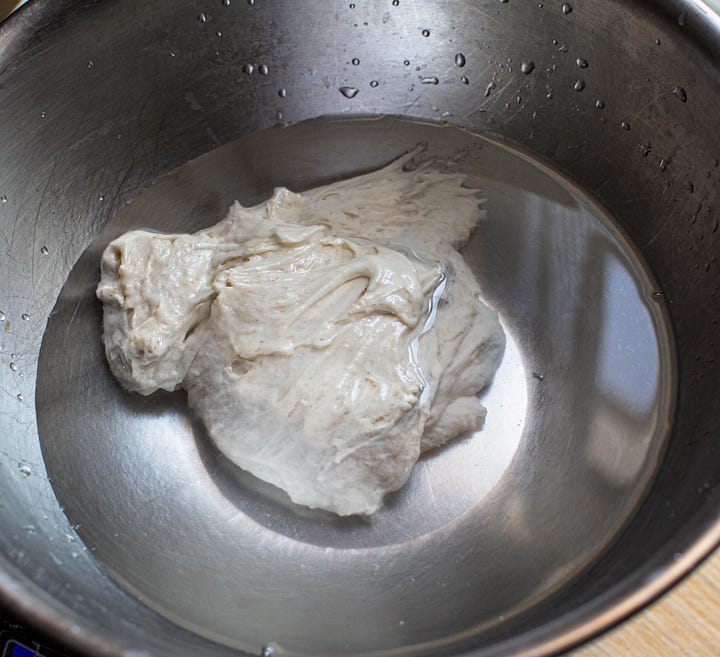

In a large mixing bowl, combine the water and stiff levain. Mix with your hands until the levain is broken up, then add the flour, salt, and yeast. Stir to combine, then work with a wet hand, flexible dough scraper, or wooden spoon, until the dough is homogenous. Scrape down the sides of the bowl and set for bulk fermentation. *For an easier time folding, transfer to a greased container for bulk fermentation.

The dough will rise for three hours, covered, folding as directed below.

Perform a bowl fold at 15, 30, 45, 60, and 120 minutes then leave untouched for the final hour.

As you perform each series of folds, you’ll begin to notice as the dough transitions to a smoother, stronger, and more cohesive mass.

Before shaping, gather the coarse bran and prepare to apply the bran crust. On a half sheet tray spread out the coarse bran, forming an even layer. Gather a mister bottle of water or a very moist towel to use for wetting the surface of the loaf.

To shape the dough.

*One note here, as this loaf benefits from a loose shape which supports a variable and open crumb. Err on the side of gentleness — this shouldn’t be tensioned like a standard boule. Instead, think of this shaping as more like a fold, allowing the loaf to retain some of the larger bubbles. Be gentle!

If making a single large loaf (note that you’ll need a large baking stone or steel, big enough to accommodate a loaf that is at least 13” or 14” in diameter), dump the dough onto a lightly floured surface. Gently stretch from the outside pressing to the middle to seal, using only the force required to keep the dough in place. For two loaves, divide the dough into two pieces and gently gather to shape and seal.

After a few quick strokes to shape, invert the loaf onto its seam side to rest momentarily and further seal, as necessary. Moisten the surface by placing the loaf onto the moist towel or by spraying it thoroughly with a mister. If the loaf feels large and tough to handle, that’s good.

Once the surface is moist, place the dough onto the coarse bran and apply the crust. I like to add additional bran on the seam side in order to make handling easier. It also adds flavor, as with the top crust. After applying the crust, place the loaf into a large lined banneton or, a mixing bowl lined with an apron, as I show in the video.

Set the loaf in a warm spot to rise for 60 minutes 75 minutes, or up to 90 or even 120 minutes in cooler conditions. As this loaf will not be scored, it’s key that it be fully risen and delicate before loading, otherwise the crumb will be overly tight and underfermented. Look for a very light feel and even some fermentation bubbles on the surface.

About an hour before the bake, preheat your oven 500°F with a stone or steel in place as well as a steaming system.

Once proofed, invert the loaf onto a sheet of parchment. If the loaf feels overly rounded or, high in the middle, gently flatten slightly so that the dough is roughly even in thickness, presenting as disc of dough about 2” high. During baking the dough will rise significantly and dome, forming a shape that is more miche-like than boule.

Bake with steam until the loaf is a deep, very dark brown, like the color of dark chocolate, about 40 to 50 minutes. If the loaf has taken too much color by the halfway point of the bake, reduce the heat to 450°F. It’s important that the loaf has ample time in the oven to dry out. In some ovens it may even be helpful to let the loaf coast to cool in the off oven with the door ajar.

Last, a note of thanks to each of you for reading, for commenting, for sending me notes, and for supporting this endeavor. It’s an indulgence for me, and I appreciate your engagement as an embrace from our community of bakers and eaters. Thanks also to Posie Brien who always has the right advice and edits for my words.

Be well,

Martin

Hello Martin. I am so taken with this bread, I started yesterday, and now about to bake. I have one question, if you don't mind:

"Bake with steam until the loaf is a deep, very dark brown, like the color of dark chocolate, about 40 to 50 minutes."

Does it mean full steam for the whole time? Or do we steam for a period at the beginning and then no?

You won that competition Martin!! Your expertise and heartfelt bread making journey has given us, your lovely book and most of all your wonderful bread making ideas. Have some fresh bran from the mill!!

BTW your apple cinnamon rolls were absolutely stunning and delicious. 🙏.