Hi folks. Happy New Year. I originally wrote this to explain the Curio, speaking to things like: Why sassafras? and Why collections? Those answers as well as this Lemon Cracked Corn, (AKA, my new favorite) recipe are below. Also, if you haven’t made the crispiest waffles, yet, you should add those to your list for the new year. Last, a sincere bit of gratitude for all of you that have engaged, shared, or simply “liked” what is happening here. All of that (plus carbs) fuels the effort. Thank you. Let’s get to the words and recipe.

On Collecting

This summer I was walking along the Kings River in Arkansas. Bent to keep the ground in tight focus with blue-green pools of the river below me, I flipped rocks with the toe of my boot. In less than an hour I had a handful of flint flakes. Sharp proof that a while back – before Christ, before the pyramids, before history even – somebody was here, making something.

A large piece of stone, half-buried in red dirt, caught my eye. Wide at the base, symmetrical, with pitted wear on the sharp end, I dug out a stone axe. If tied to the Dalton point arrowheads occasionally found in the area, it could be as much as 10,000 years old.

Everything stopped. I turned the tool in my hand. Who was here on this very hill seeing the same mountains, soaking the same sun, so long ago? Their work, their tool, resting in my palm. A connection, now to then.

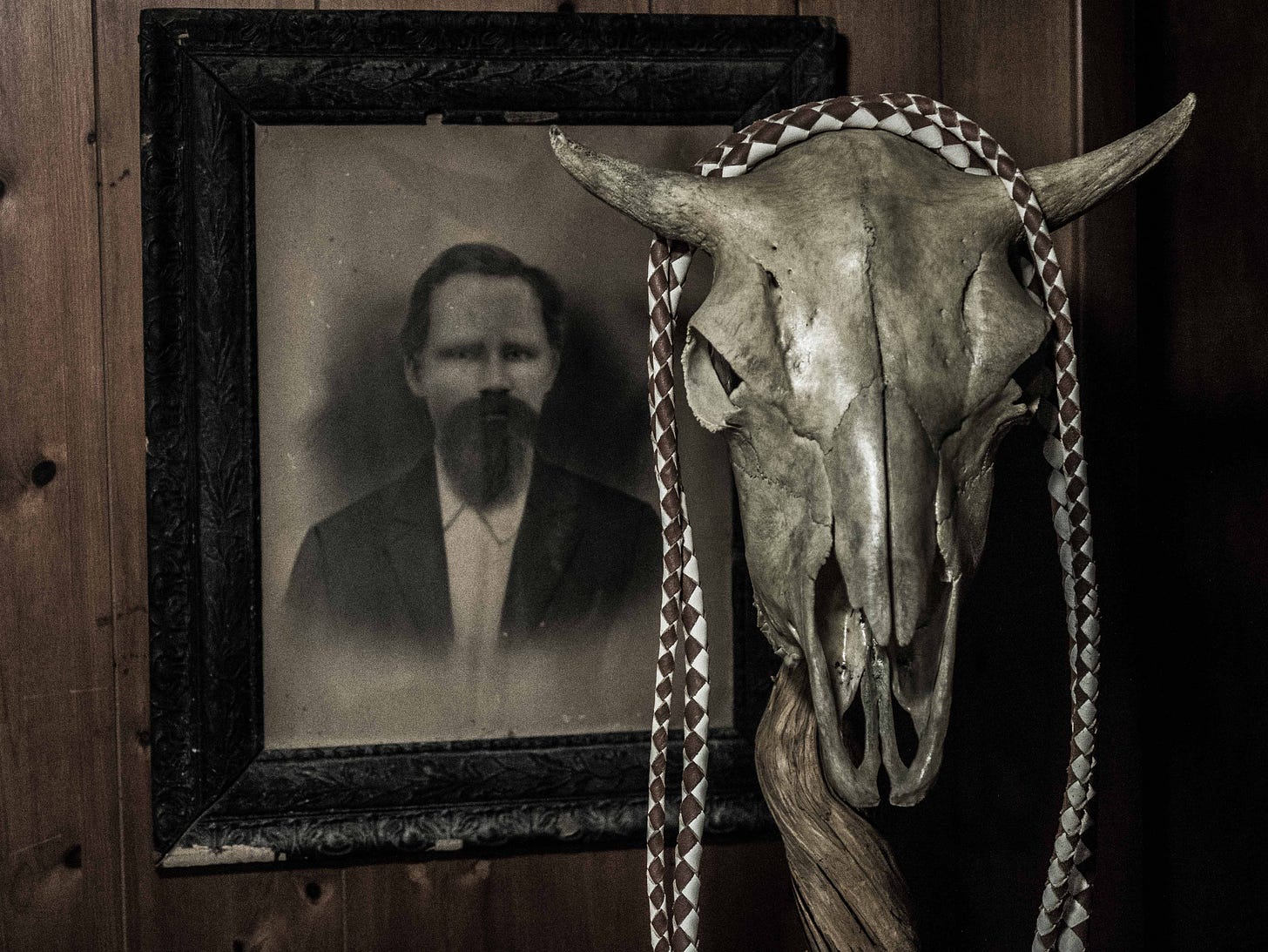

My grandmother kept a cabinet of old things in her front hallway. A curl of hair from the 1800s, chunks of civil war cannon shot and minié balls, binoculars with a bullet through the eyepiece, a child’s skull. Everything, every last piece, sleeping behind glass, waiting to exhale stories in musty sentences as she opened the case for us to look at.

I’m drawn to old things for reasons both clear, and unknown. Like cellar holes collapsing and grown over, remnants of what was can mark a place, keeping time in its own way. When we go, objects are the echo that remains, saying, “We were here. This is what we made.” If I can’t understand loss or the mystery of this spirit that enters and exits so damn quickly, somehow, through collected things – old quilts, flakes of flint, or oil-stained notecard recipes – I get closer; if not to the warm hand itself, to the thing it made. That helps.

My mother holds her own collections. “Marty, remember that?” Yes, mama. (50 years of the same bowl for mixing bread, the same container for storing flour, the same recipe, the same knife to cut that same bread.) If you’re new to her house, set time aside to hear the history of almost everything … or to at least have a piece of toast.

And I have my keepsakes, too: old perfume bottles, brooch pins, pocket knives, belt buckles, arrowheads, clay pipes…

But I’ve also branched out a little: stories, recipes, thoughts about how the simple act of making and sharing food might bind us to whatever we came from. And smells: my grandmother’s house as we entered for a holiday meal – roasting turkey, molasses pie, pecan pie with whiskey, the small tobacco keg of horehound candy on my grandfather’s bookshelf.

And, among all of this, something deeper: a root. Fixed in the dirt of the mountains and hollers I come from, sipping sweet springs and pumping its soul into a smell that fixes a thing – roots, bark, leaves, and twigs – to a place, is Sassafras Albidum.

Also known as “cinnamon wood,” from gumbo file to dugout canoes, and Sasparilla (“root beer”), the plant, Sassafras, which grows from small bushes into trees, can be identified by the shape of its three leaf types. One, a mitt with a thumb, another which is merely oval-shaped, and a third which has three lobes, is abundant in the Ozark Mountains. As a kid, running in those hills, I’d pull the plant when I found it and cut the stalk, stuffing the root into my pocket. There, I’d hold it like a gold coin, banking on the knowledge that a smell so perfect could be withdrawn at any moment.

To fully describe my connection to this plant, “totem,” the anglicized form of the Ojibwe word, meaning, “a depiction of an animal or plant that gives a family or clan its name and that often serves as a reminder of its ancestry,” is the best I can do; it’s what I am, where I come from, it fixes a thing to a place, tying me to the very ground.

So, welcome. This is the Sassafras Curio. My collection, my cabinet by the door.

Lemon Cracked Corn

Grits, lemon zest, honey, buttermilk — these aren’t things I’ve combined in a bread before … but I should have. The malty corn balances a toasty bake, citrus highlights brighten the scene, and buttermilk softens the crumb. I’ve fit the entire process into a single afternoon and it’s a new favorite. Enjoy the BREAD.

Martin

I just made this! Ordered the grits as instructed from Marsh Hen Mill. Received it yesterday, made the loaf this morning. I wasn’t sure what to expect since I’ve never had grits before. So, two things, I really like grits. Second, this bread is ridiculously good. The lemon zest made the bread smell so good. Thanks for referring me to this recipe (from your latest post). Just have to keep working on shaping and the scoring- time to revisit your videos.

Absolutely beautiful! I totally understand the connection and have a strong pull to sassafras for the same reason. We had them all in our yard and on my elementary school playground and it always brought me so much comfort.