This is a story from the bicycle, biscuits, and banjo adventure I had in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas in 2018. On that trip I cold-called homes, knocked on doors, and baked biscuits for strangers in my home state. If you enjoy this piece, also have a look at Evening in Red Star, and Afternoon in Jethro for more stories from the trip. And, if you’d like to bake something that’s roadshow-inspired, try the spicy, cheesy firecrackers in the Red Star piece or these Sourdough Biscuits which also include a recipe for butter beans. Enjoy the story!

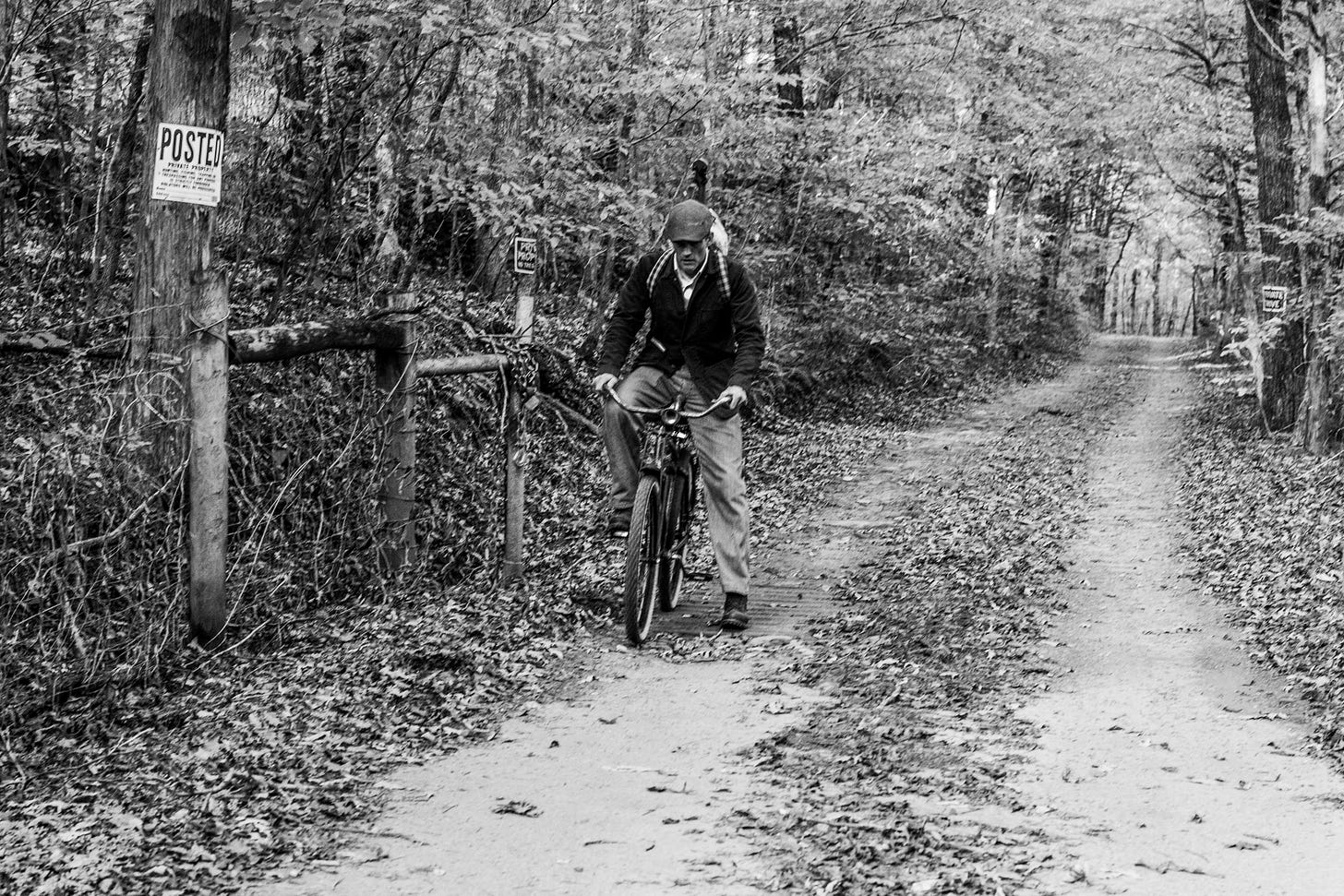

The path to Richard Howard’s house is more tunnel than road. Shag-bark hickory and black oak walls curve to leaf ceilings, shading a single lane of red dirt traffic below. Rolling into daytime darkness I pass orange signs. “No Trespassing,” “Keep Out.”

This land, deep in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas, has been in Richard’s family since the 1700s. Bordered by two million acres of national forest, the hills, trees, and scattered residents here form the barely visible town of Mountain Creek, named for a spring-fed crease which falls from Spy Rock and drains out the bottom of the valley into the Mulberry River.

Bouncing down the rutted road is a clanky affair. I have a wicker basket strapped to the back of my bicycle with a pot of beans, corn grits, and a flask of cream: good calling cards out here on the forgotten roads of Arkansas. Each jostle—each bump and swerve—plays the basket like a one-man band.

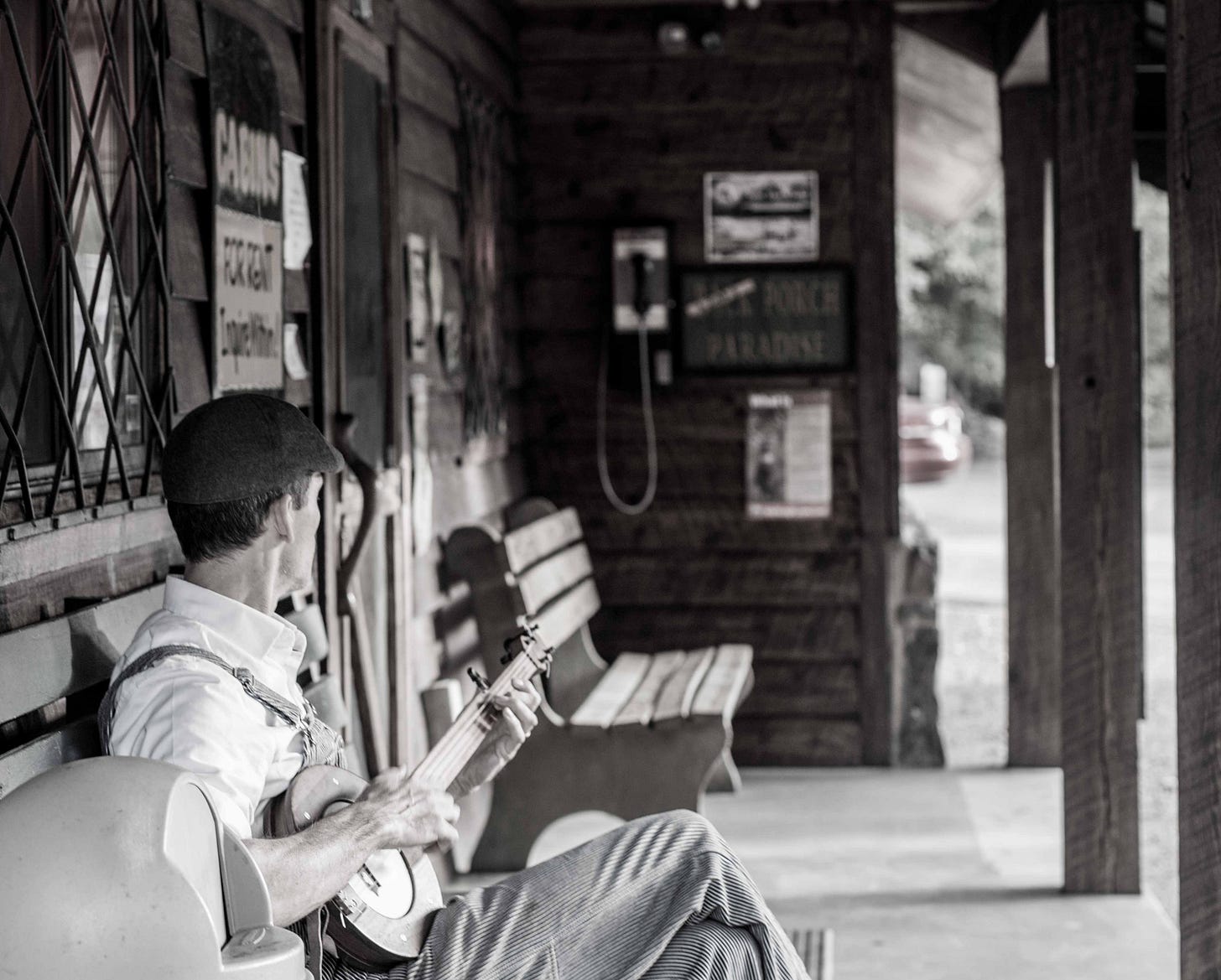

I met Richard this morning in front of a canoeing outfitter on the Mulberry River. I was there playing my banjo on the front porch and laughing to myself about the Deliverance-worthy combination of deep woods, canoes, and twangy tunes. Richard pulled in and parked his truck as close to the door as possible. A veteran of Vietnam and 29 surgeries, he recently had a leg removed. Though still mobile, he doesn’t get around like he did as a football star at Ozark High School. A woman ran a doughnut and a cup of coffee out to him. “He’s a regular,” she said.

My dad, who’s never met anyone he doesn’t know, walked over to Richard’s truck and started talking. It turned out that they were in Vietnam at the same time. I watched for a minute then stopped playing and made my way over to introduce myself. “I’m in the area, riding my bicycle, playing music, and collecting stories. Can I make you a meal?”

He balked at the offer—he’d just had work done on his mouth which left few teeth to eat with. I suggested soft beans and grits—he accepted, I got directions.

The how and why of my time down here is complicated. The short story is that this is where I began. This state, these mountains, my accent; junk-piled yards, snaking creeks, greening ponds, all part of me. But years ago, I left. Now, mostly, I feel a million miles away. I’m back to see if it’s really that far.

Riding up Richard’s lane, I pump and strain to make the old bike climb one last rise past cellar holes and rusting tractors until the grade levels and I can coast into the yard, swinging my leg over the seat as I slow.

I see Richard on a deck that overlooks a pond, fishing from his wheelchair. I gather the view. On my right is what looks like the contents of an old homestead. Everything collected and piled, from a wringer washing machine to a millstone, piles of old bottles, farm tools and seemingly one of everything else that was ever useful. Everything but the home itself. As we talk he relates that the homestead had to be torn down because the newer house he’d built next to it was placed too close to be insured by the bank. And so, as it seems to go, the old was kicked over for the new.

I lean the bike against a tree and walk to the deck. Fish and flies at the water’s surface parry and thrust while clouds, pink on their western edge, drag shadows across the peak of Spy Rock. Beyond the pond his teepee sits on a knoll. He explains that he hand cut the log poles and, after several tries, found the proper orientation between the structure and the mountains. “Do you have a spiritual connection to the teepee?” I ask. “There’s something about it,” he says in his gentle drawl. “There are stones and stuff that I have found here on the farm...”

In a hushed voice he goes on to tell of a day when he was walking in the dry bed of Mountain Creek. He stepped over something which, after he passed it, “called me back,” he says. He retraced his steps and found the visible point of something pure black—darker and heavier than the native rocks and silt. He dug it out and cleaned it off—what emerged was a perfect triangle. With his forefingers and thumbs together, he wedged it into the void of his fingers. There was something about it—a power, an energy. He kept it. Years later, he showed it to a Cherokee elder who then pulled him aside to quietly identify it as a healing stone—the largest he had ever seen. It was carved from a star.

My stomach is growling. I think of the pot of beans in my basket. The evening prior I heated garlic cloves and butter over a campfire. I added butter beans and spring water and seasoned them with smoked jalapeños and a cut up beefsteak tomato, both given to me by a farmer I had visited. I banked orange coals under the pot then added meat—pulled off smoked pork ribs. The pot gurgled under bright stars, the beans turning themselves as the tomato melted into the liquid.

“Are you hungry, Ritchie?” I ask. “I could eat,” he says. We go inside and I paw through a sink of dishes to find a pot that will hold grits for two people. I add water, cream, and salt, and bring it to a simmer. I pour in the dry grits and stir as they thicken. I wash two serving bowls and spoon in some of the grits. They pool slightly, and I top them with a ladle of beans, pushing it down to form a well where they can sit. I go back for additional likker from the pot; it breaks the ring of grits, forming a moat at the edge of the bowl. We eat on the deck, overlooking the pond as daylight wanes.

Before I reached Richard’s road, I sensed that I was approaching something. Richard had the energy of a seer. A force. Someone connected to the before and the beyond. Sitting down with two bowls and two spoons, I only want to hear him talk. He obliges.

We eat through seven generations of boom and bust. Murder (a great aunt, four years old, kidnapped as ransom and killed for a gold hoard that was never found), betrayal (a brother sold the family land out from under another brother, generations of fallout), death. War. Richard left upon high school graduation to fight in Vietnam, using skills he learned in the hills and hollows to survive; over 50 years of treatment since and still no healing. Home. His mama’s legendary cooking, especially her biscuits; “Nobody’d made any like that,” he says, “and nobody [has] since.”

Out of this—all the loss and the heartache—the hardest thing is how his world has changed. Like “getting hit in the face with a shovel,” as he tells it. “Cass used to be a community,” he says. “You helped each other out.” He clears his throat, as he chokes up. I pat his back. “People were closer,” he continues through tears. “I hate that it’s gone...it’s like [a] death knell.”

As the light changes from dusk to dark, bats and night birds swoop the pond’s surface. Locusts whirr in arcs of sound as I gather our bowls and head inside. Richard wants to show me a homemade banjo built from a pressure cooker and a piece of hand-carved maple. He won it from the original owner in a trade for 200’ of 4” pipe. I hold it. What could one put through a pipe that’s worth more than this banjo? The ingenuity of construction is a revelation—mountain people have a knack for making everything from nothing.

I twist the old tuners, coaxing rusty strings to order. Richard watches. He doesn’t know how to play, but this banjo—a fixture at family and community gatherings eras ago—means everything to him. It’s a time capsule, hoarding memories of people and days long gone.

I land in an old tuning and brush the strings once, twice. The tone is deep, muffled, muddy; you’ve been asleep so long, I think. But two of the strings retain some vitality and I use them to play a clawhammer version of the Scottish traditional, “Loch Lomond.” The refrain is familiar, “You take the high road, I’ll take the low road, together we’ll meet in Loch Lomond.” I continue, looking for an inner verse. “Too sad we parted in yon shady glen, on the steep, steep sides of Loch Lomond. Where the broken heart knows no second spring, resigned we must be while we're parting.” His smile is as wide as the pressure cooker, which slowly finds its way through dust and years to ring against the walls of his living room.

It’s time to go. I slowly pack up and say, “I’m gonna give you a hug, I hope that’s ok.” I squeeze him hard. The embrace is tearful.

Before I leave he wheels out to his truck and reaches for something in the console. I see that it’s heavy, and precious. His hands unfold the swaddled cloth, and there, black, shiny like obsidian, metallic, and triangular, is the healing stone. Holding it, feeling its weight, I think of the hands before mine, the lives around me, and what I might heal, if I could.

Sadly, Richard Howard passed in early 2020. I only knew him for a single day, but I feel like we made it count. Rest in peace, Ritchie.

Here’s a link to a longer version of the same story which I read for The Kenyon Review.

Thanks for sharing this beautiful article. I loved reading it and I'm looking forward to reading it again.

Martin, this is so touching. So much love in here. And it's wild to read how you were cold-calling homes, baking biscuits for strangers! Wow. Strangers...and after all, was it really that far, your answer embedded. Thank you so much for writing this.